British punk culture has a long and varied history of campaigning against the bomb — spitting in the face of war.

By the late 1970s, Britain was in political and social crisis. Economic recession, mass unemployment, class division, and a growing fear of nuclear war shaped the everyday lives of a disaffected youth. Out of this bleak backdrop exploded punk, a movement born not just from musical rebellion, but from a sense of political urgency. While often caricatured as nihilistic or chaotic, punk was deeply rooted in critique—and one of its most powerful targets was the nuclear arms race.

The late Cold War era saw a dramatic rise in nuclear tensions between NATO and the Eastern Bloc. In the UK, the arrival of American cruise missiles at bases like Greenham Common, and the renewed threat of Mutually Assured Destruction, sparked national alarm. CND, already active since the 1950s, began to regain visibility in the mainstream—organizing marches, teach-ins, and peace camps. But for many younger people, particularly those immersed in punk, traditional forms of protest felt too tame.

For punks, the nuclear issue wasn’t abstract. It was personal. The idea of 'no future' wasn’t just a slogan—it was an expectation. If the bombs dropped, they knew they’d be the ones with no shelters, no chance, and no say. Their music reflected that. Nuclear war, radiation, state secrecy, and militarism were frequent themes in punk lyrics, zines, and art.

The most significant bridge between punk and anti-nuclear protest was the anarcho-punk scene. At its centre stood Crass, formed in 1977. Crass didn’t just play music—they lived their politics. Based at Dial House, a self-managed anarchist commune, they released records through their own label, published radical literature, supported direct action groups, and lived by non-hierarchical, pacifist principles.

Crass records like “How Does It Feel (To Be the Mother of a Thousand Dead?)” directly attacked Margaret Thatcher’s war policies and Britain's nuclear alignment with the U.S. Their 1981 single “Nagasaki Nightmare” was a sonic assault on the morality of nuclear weapons. The artwork featured a stark, militarised reinterpretation of the CND peace symbol—warped and threatening. Crass took peace and made it confrontational.

Other anarcho-punk bands like Subhumans, Conflict, Amebix, Zounds, and Flux of Pink Indians also addressed nuclear fear head-on. Conflict’s record “The Ungovernable Force” was an entire manifesto wrapped in hardcore punk—denouncing war, capitalism, the monarchy, and nuclear destruction in equal measure. Zounds’ track “Subvert” challenged listeners to dismantle the very systems that made the bomb possible.

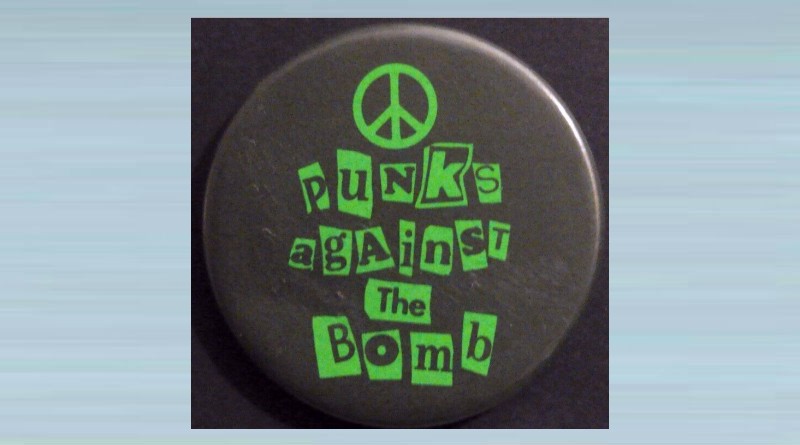

Visual identity was as important as sound in punk’s resistance. The CND symbol, once soft and associated with 1960s peace marches, was reappropriated. Punks wore it on leather jackets, painted it on patches, scrawled it in graffiti, and embedded it in flyers. It became harsher, blacker, and more militant—often paired with slogans like “No Nukes,” “Destroy Power Not People,” or “Fight War Not Wars.”

DIY culture was central to the scene. Badges, often homemade, became tiny tools of dissent. Many combined punk imagery—skulls, safety pins, mohawks—with anti-nuclear messages. Zines like Kill Your Pet Puppy, Toxic Grafity, and Chainsaw published guides to CND marches, exposed government hypocrisy, and connected readers to protests, squats, and support networks.

Punk didn’t just comment on politics—it participated. Bands played benefit gigs for CND, squats held anti-nuke workshops, and punks joined protests en masse. At demonstrations like the Stop the City actions (1983–84), crust punks were at the forefront—blasting music from portable amps, clashing with police, and turning protest into performance.

The Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp became a powerful site of feminist anti-nuclear activism. Although not a punk space per se, it attracted many women from punk and alternative backgrounds. Anarcho-punk feminists, inspired by both political radicalism and DIY ethics, were drawn to its non-violent resistance, its campfire politics, and its open challenge to militarism.

Meanwhile, Glastonbury Festival, especially through the 1980s, became a convergence point for punk, CND, and alternative culture. In the Green Fields, anti-nuke theatre clashed with anarcho music, and badge stalls sold peace symbols next to punk patches. Bands like The Damned and The Stranglers played alongside folk artists and political speakers. Even if the festival softened over time, it captured the spirit of the era.

The punk era gave the anti-nuclear movement a new edge—a visual, sonic, and emotional force that traditional campaigning lacked. It refused respectability, mocked authority, and turned despair into defiance. Though punk changed shape in the 1990s and 2000s, its anti-nuclear legacy lived on in the DIY scenes, climate justice movements, anti-globalisation protests, and even in today’s post-punk and crust revivalists.

The peace symbol survived too—still scrawled, still stitched, still worn. But in punk’s hands, it meant something darker, more urgent. It wasn’t just peace—it was resistance. Not “give peace a chance,” but “take power down.”

Unlike the glossy, mass-produced campaign badges of mainstream politics, punk badges were often made using rudimentary badge presses, photocopiers, and collage methods. Bands, squat collectives, and small DIY operations cranked them out by the hundreds in squats, bedrooms, and zine distros. This wasn’t merchandising—it was agitation.

Many badges featured reworked peace symbols — not in the clean, hopeful style of 1960s hippies, but in stark black-and-white, surrounded by barbed wire, mushroom clouds, or anarchist slogans. Some badges inverted the logo, turned it into a bomb, or merged it with the circled A of anarchy.

Punk badges were visible signals of resistance—worn on jackets, army gear, bags, guitar straps, and boots. At punk gigs, badge stalls offered anti-nuke messages alongside band emblems. In squats and at protests, they were handed out, sold cheaply, or included in zines and mixtapes. Each one was a miniature protest sign.

Limited-run badges created for benefit gigs or specific protests often became collectible. Some were made in runs of fewer than 50, blending political urgency with underground craft.

Badges were also a response to pop branding. Instead of Madonna or Wham!, punk offered badges that said “No More Hiroshimas” or “Destroy the System.” The visual clash of peace signs with skulls or gas masks wasn’t a contradiction—it was the point. Punk turned peace into confrontation, rebellion, and critique.

Unlike official campaign buttons, these punk badges are often raw, politically charged, and unique to specific moments in the subculture’s history. They are small artifacts of a time when protest lived on the lapel as much as in the street.

☮️ Organisation: Original Punk Bands

🕰️ Age: Late 70s -early 80s

💎 Rarity: 5-10/10

⚙️ Material: Mostly tin, with a few exceptions

📏 Size: Various

🎨 Variations: Various

💰 Price Guide: £20 - £50 is typical but prices can go much higher

📌 Top Tip: Original punk badges are heavily copied and / or reissued, so don’t be fooled! Check the materials, printing, and design details carefully.

Original punk badges from the late 1970s to the early 1980s have become highly sought-after collectibles, prized not just for their aesthetic impact but also for the cultural and political significance they carry. These small items capture the rebellious energy of the era, from the DIY ethos of anarcho-punk bands to the visual defiance of anti-nuclear and anti-establishment messages. Collectors often value badges that retain their original materials, designs, and colors, as these convey authenticity and the tactile connection to a formative period in punk history.

However, caution is essential when searching for genuine originals. Many of these badges have been reissued or reproduced over the years, sometimes decades after their initial release. While reproductions can be visually similar, they often differ in quality, printing, or backing, and may not hold the same historical or financial value. For collectors, knowledge of the issuing bands, the original production methods, and subtle design details can make the difference between acquiring a true piece of punk history and a later copy.

In terms of rarity and value, most original punk badges are relatively scarce, especially those produced in very small runs for independent gigs, benefit concerts, or DIY zine distributions. Prices can range from £20–£50 for more common originals to several hundred pounds for iconic limited run or one-off badges from bands like Crass, Conflict, or Subhumans in excellent condition. Rarity indicators include limited production numbers, unique designs, unusual materials, or provenance linked to specific events or tours. Collectors are advised to buy carefully, cross-check references, and when possible, seek verification from trusted punk memorabilia communities.

Coming soon.